Fujii Defying History, Convention One Fight at a Time

Defying History

Tony Loiseleur Sep 30, 2010

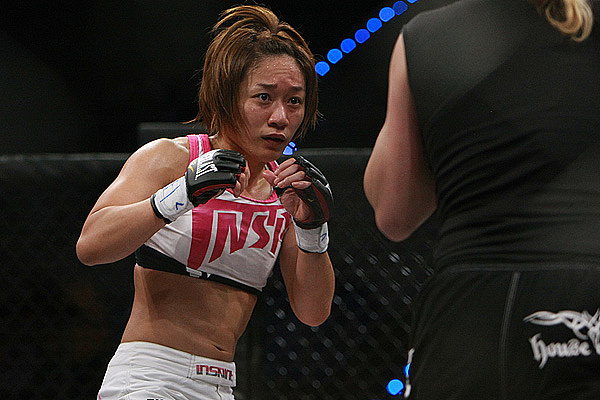

Megumi Fujii file photo: Dave Mandel | Sherdog.com

Japan’s Megumi Fujii is considered by most the best pound-for-pound best female mixed martial artist on the planet. It’s a distinction earned by the dominant way in which she has amassed a flawless 21-0 record. However, the undefeated streak has taken Herculean effort to achieve in and of itself.

Advertisement

Though Gina Carano is now more movie star than MMA fighter, Miesha Tate is willing to do sexy spreads for fight magazines and Cristiane “Cyborg” Santos was reportedly considering Playboy, the gendered differences in western MMA have not completely hindered women’s ability to earn significant paydays and athletic distinctions. These women have acquitted themselves in the cage, fighting under -- for the most part -- the same rules as their male counterparts and have reaped financial and critical success that no woman in Japanese MMA’s long history has ever achieved.

Watch a women’s MMA fight in Japan, and the paternalistic

compromises are clear: shortened fights, some are three

three-minute rounds while most are two five-minute rounds; awkward,

oversized gloves; over-officious referees who are quick “save”

women from harm before submissions are fully applied or when

strikes are not even landing. Ground-and-pound -- an essential

element of MMA -- is almost entirely verboten, save for a few

marquee bouts.

Titillating pictorials overtly sexualize Western female fighters, but the cosmetics and bikinis are traded in for cornrows, board shorts and rash guards when they step into the cage. In Japan, MMA panders to gender-normative stereotypes of femininity with its in-ring dress and promotional aesthetics. Pre-fight promotional videos typically focus on a fighter fabricating her colorful costume, styling her hair, getting her nails done or working at her day job -- implying prizefighting is only an eccentric hobby -- rather than focusing on training, fighting or any athletic narrative.

Take for instance former Deep champion Hisae Watanabe, one of the Japan’s biggest female fighting stars. In spite of her extensive fight experience, Watanabe – who has actually fought with make-up on for most of her career -- has been routinely shown in pre-fight vignettes going to hair and nail salons, shopping for clothes or semi-suggestively eating a strawberry sundae.

“[Our promotion] is about conveying the charm of women doing MMA,” says a public relations representative with the Japanese women’s MMA promotion, Jewels. The implication is clear -- appeal is drawn from the spectacle of women engaged in an otherwise masculine pursuit, rather than showcasing athletes competing earnestly.

Roots Take Hold

The root of this viewpoint lies in Japan’s history with professional wrestling. Men’s pro wrestling became a mainstream fixture in post-World War II Japan by showing the hometown audience that, though they may have lost the war, the indomitable Japanese fighting spirit could still defeat any Westerner in single combat. Pro wrestlers such as Rikidozan -- who was ironically an ethnic Korean -- were hyper-realizations of Japanese identity, defeating foreigners through martial prowess and fair play, two attributes that “dirty-fighting” Western wrestlers were imagined to be devoid of, thanks to the theater of pro wrestling.

From a physical and, perhaps more importantly, moral standpoint, professional wrestling celebrated an edifying self-characterization of the Japanese, bolstering pride and reaffirming national identity at a time when the country needed it most. As sports sociologist Lee A. Thompson claims in citing cultural anthropologist Clifford Geertz, pro wrestling was meta-social commentary to the Japanese -- “a story they tell themselves, about themselves.”

Though its message differed, women’s pro wrestling was a similar social project in being demonstrative of femininity. Its heroines and villainesses were archetypal caricatures of pro- and anti-womanhood. The “faces” fit the heteronormative understanding of what the Japanese perceived to be properly feminine -- young, nubile and morally pure -- while the “heels” were aberrations of that model -- physically imposing, butch and aggressive.

This essential structure of women’s pro wrestling was founded upon Japan’s cultural and social understanding of sexual characteristics and responsibilities. In Vera Mackie’s “Feminism in Modern Japan,” Mackie notes the lack of a native term for “gender,” and that before its introduction in the 1970s, Japanese understanding saw “two categories of people -- men and women -- who had bodies distinguished purely by their reproductive capacities.” This understanding led to a dichotomous conception of behaviors and responsibilities exclusive to sex. Note the National Eugenic Law, which during Japan’s Imperial period exerted state control over the reproductive body, regulating female responsibility as the nation’s reproductive force.

Intense state control over the female body diminished in the post-war, but social sentiment remained largely the same. According to Atsuko Suzuki’s “Gender and Career in Japan,” when post-war Japan achieved economic prosperity, the “ideal household” recast female responsibility from that of broodmare to domestic homemaker. Husbands were shouldered with the financial responsibilities of a family, “freeing” women from having to enter and remain in the workforce. Though less severe a distinction, the life trajectory of women in post-war Japan remained the same, leaving little room for careers that did not terminate upon marriage or activities that did not prepare women for the roles of “wife” and “mother.”

Women’s pro wrestling was made keenly aware of this when the growing domestic television audiences of the 1960s protested that pro wrestling was not a proper feminine pursuit and was thus unfit for public consumption. It was not until the 1970s when teenage wrestlers-stroke-pop singers like the 16-year-old “Mach” Fumiake Watanabe and the similarly young Jackie Sato-Maki Ueda tag-team “Beauty Pair” became crossover, mainstream celebrities that women’s pro wrestling gained any kind of traction. Promoters further continued to ensure that proper gender roles were adhered to: until the 1990s, women’s pro wrestling in Japan maintained a mandatory retirement age of 26, out of consideration for future marriage and family-raising.

Stunted Growth

Japan’s longstanding ties to the pseudo-sport thus made it impossible to disentangle MMA from its pro wrestling roots. In speaking with promoters of today’s most prominent Japanese women’s MMA promotions -- Deep, Valkyrie and Jewels -- all admit that this connection to professional wrestling and the social conventions it supported is what has kept women’s MMA from growing over the past decade.

However, none of them are ready or willing to commit to pushing an agenda of change, though they promise that, depending on their audience, things may be different in the future. They maintain their staunch adherence to the promotional model and practices of women’s pro wrestling since it has a proven history of success. Deep promoter Shigeru Saeki was himself a pro wrestling promoter, as was Daiki Shinosaki, the man that created the now-defunct landmark promotion Smackgirl.

Related Articles