Ian McCall's Violent Delights

Shakespeare Comes to the Cage

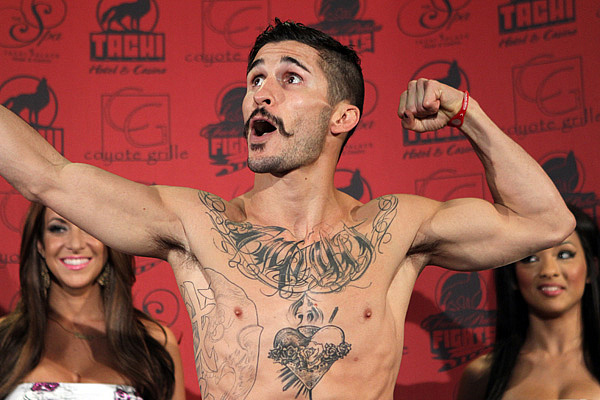

Ian

McCall’s tale might have been penned by The Bard himself. | Photo:

Jeff Sherwood

Few things are more coveted in sports than a champion with a human interest story. This is especially true of prizefighting, a realm of athletics that is both individual and attracts unique and engrossing personalities.

Prologue

In recent months, MMA has started to gaze more intently at the 125-pound division, knowing that the weight class will be featured in the UFC’s Octagon before long. Fortunately, the division already has a magnetic torchbearer with a galvanizing story.

Advertisement

These are 12-and-a-half stories about the man.

Act I: First Impressions

The first time I met Ian McCall face-to-face was in May. I was fortunate enough to call his bout with Dustin Ortiz at Tachi Palace Fights 9. McCall was cresting high after upsetting then-consensus No. 1 flyweight Jussier da Silva in February.

When he sat down in front of me for his pre-fight production interview, he looked dreadful. Just two hours before weigh-ins, he just barely had enough saliva to speak. The flesh of his face had sunk, and his cheekbones jutted through his dehydrated face. And yet, when he spoke, he did not equivocate.

“Oh, Sherdog? Love you guys,” he says, smiling through his cotton mouth. “Too bad you’ve got a bunch of Japanese fighters ahead of me in your rankings.”

Listening to fighters beef over rankings is nothing new. I entertained his chiding, but he was not too concerned, as he told me he was seeking a more proactive approach: McCall told me that rankings did not matter to him, because he would beat everybody put in front of him, no matter what side of the Pacific they fought on.

McCall dominated Ortiz in dynamic, versatile fashion. After the bout, he stood outside his locker room trailer in the midnight dark. A teammate asked him what was next for him, knowing he had recently tried out for the bantamweight division on “The Ultimate Fighter” Season 14.

“Right here; it’s going to be Montague next. I feel like this is my niche. I can be the best here. Plus, those dudes were huge,” he says, elongating his final word for emphasis.

I did not see McCall until three months later. It was, again, before his production interview. I asked if he would be comfortable doing a second interview for Sherdog after the hype video sit down.

“Sure thing, sweetheart,” he says with a grin, “anything for you.”

Few could ever be so welcoming and so disarming with an inappropriate pet name.

Act II: The Mustache

When we do sit down to chat, I compliment McCall’s mustache. Since May, he has grown out his ’stache into handlebars, curling the ends like a vaudeville villain.

“One day, I just wanted to grow one,” he explains. “It turned into this glorious thing.”

I tell him I’m impressed, since very few people can pull off a simple mustache, let alone a more exotic version of one. Although it was clear he had grown it for ironic purposes, it was, somehow, 100 percent appropriate.

“It works so well,” he says. “People say I look good in it. I meet so many people who compliment it, saying, ‘I don’t like mustaches, but yours looks good.’”

I ask him if he has ever seen pictures from high-level beard and mustache competitions, and we briefly discuss some of the more bizarre and bold facial hair choices we have seen. But mustaches are not solely a goofy, sarcastic interest for McCall. He tells me about how his six-months-pregnant fiancée, Shay, had been inspired by his mustache. After he started to grow his hirsute accessory, she would bring home mustache-themed items. First it was pillows. Then fake mustaches. These same fake mustaches would make an appearance on fight night, as several people in McCall’s cheering section sported them in support of their fighter.

However, the piéce de résistance came shortly after, when his fiancée arrived home one day with a likeness of his mustache tattooed on her left ring finger.

“She’s just the best, dude. Right now, it’s all mustaches. Everything mustache!” he beams, making “everything mustache” sound like some sort of political slogan.

I see his fiancée later, walking through the hotel. Just like McCall’s questionable mustache improbably suits him, it is hard to imagine a more fitting engagement ring for his bride-to-be.

Act III: Meet the Chihuahuas

Later that night, I ask McCall if he has a few minutes to talk. He tells me he would love to, but he has some trepidation. His fiancée is asleep in their hotel room. He is conflicted: he wants for the mother of his children to sleep but is eager and excited for me to meet his pair of Chihuahuas, Sadie and Tony.

“But man, you have to see them!” he urges, sensing an impasse.

I invite him to my room and assure him that, even if I cannot meet them, I want to hear all about them. As a pet-less bachelor, I cannot speak on whatever similarities might exist between dog ownership and parenthood, but if passion and joy translate, McCall will be a highly doting father.

McCall and Shay have cards for their dogs to inform others that they are therapeutic animals, crucial in moderating their stress and blood-sugar levels. McCall admits it is a ruse, simply so they can take the animals with them everywhere in public.

“Sadie actually has hypoglycemia,” McCall says with a smirk, fully aware of the irony. He tells me about how he has treated her seizures with honey and shows a considerably parental-type pride with his ad hoc prescription. McCall, who professes an open love for the Animal Planet, displays all the traits of a tried-and-true animal lover, including personifying his pets.

“After we had Sadie, it was hard because we had to take her everywhere with us,” he says, unaware that he describes his dog as though his girlfriend had given birth to it. “So, we had to get her a friend to hang out with so we could leave the house.”

I laugh, but, as if McCall senses that my laugh is simply to be polite, he continues.

“Seriously, though, they’re like best friends now. It’s like they’re getting married, too. They’re in that honeymoon phase,” he proclaims.

Act IV: Addictions

“I was in a gang,” McCall says with a laugh.

“What kind of gang?” I ask.

“Like, a white-kids-who-want-to-fight gang,” he says, shaking his head with an adult-level of embarrassment.

J.

Sherwood

McCall has put his old life behind him.

He tells me candidly about his use of Oxycontin, Xanax and GHB and his prior obsession with what he calls “whoring [himself] out to the world.” McCall tells me about DEA agents raiding his apartment while he was casually eating a bagel. He rolls his eyes in explaining how he was arrested for having a syringe. Despite the fact that one of the arresting officers was a former jiu-jitsu training partner, he refused to buy McCall’s assertion that it was to drain his cauliflower ear.

Rehabs and relapses and overdoses. Having sat 18 inches from the cage when McCall, in tip-top shape, bulldozed a talented Ortiz in May, it seems hard to imagine that an athlete that sharp could have put his body through such torment. He seems so enthused when he talks about his past, not because of a fondness of memory, but because it is over. McCall clearly has an addictive personality that he now prefers to channel at home -- and in the gym.

“I train two, three times a day, and people always tell me, ‘Man, you gotta slow down. You’re going to overtrain,’” he says, shaking his head to refute the hypothetical statement. “They say, ‘Holy cow, you’re in great shape. You’re going to burn out.’”

He shakes his head again, twisting his lips and smugly shaking off the criticism.

“And at home, it’s the same thing,” McCall says. “I just want to be dedicated to this one woman now; I never wanted to marry someone before.”

Act V: The Road to MMA

The 5-foot-5 McCall is enveloped by the oversized hotel armchair. He sports a mesh-back trucker cap; a black handlebar mustache adorns the otherwise white foam front. In a pair of sandals that reveal badly chipped toenail polish to match his badly chipped fingernail polish, he hardly looks like the torchbearer for an entire MMA division.

McCall’s road into MMA is a familiar one. He did karate and kung fu as an undersized youth. He laughs at the wisdom imparted on him by his kung fu trainer -- a man he refers to as “Sifu Bill” -- with a palpable love in his voice.

“He used to tell me that I had a ‘red zone’ and that if somebody came in that space, I needed to know how to act,” he says, tracing a two-foot radius in the air around his body.

Like other MMA fighters, McCall wrestled -- at Dana Hills High School and later at Cuesta College in San Luis Obispo, Calif. However, his reckless nature limited his success. It was little different when he began training MMA. McCall started at Chris Brennan’s Next Generation, but drama within the gym caused an early exit. He then turned to training with Brennan’s first-ever black belt, Jeremy Williams, at Apex Jiu-Jitsu. However, Williams’ personal demons clashed with McCall’s own.

“He knew I was doing drugs and basically told me that it just wasn’t a good fit for me at the gym,” McCall says. “It hurt, but I understood. He said, ‘For our friendship, you can’t train at my gym anymore. It makes us look bad. I’m sorry.’”

On May 5, 2007, Williams was found dead from a self-inflicted gunshot wound, less than a month before his 28th birthday.

“When I first went to Colin [Oyama]’s, they all knew,” McCall says. “It was hard at first, but I knew a few guys there, like Rob Emerson, and, eventually, I just became part of the family.”

Oyama first came to MMA prominence in the early portion of the last decade, training then-UFC light heavyweight champion Tito Ortiz and Quinton “Rampage” Jackson. After his two star pupils left his charge, his salad days as a trainer seemed over. However, when Oyama aligned with Brazilian jiu-jitsu standouts Giva Santana and Fabio Nascimento, the muay Thai-oriented gym slowly began to reinvent itself as a player in the MMA game.

“It’s huge having those two,” McCall explains to me when I ask about the impact of the Lotus Club duo. “They’ve made us all so much better in the gym.

“Every time I see a Brazilian I don’t know, they respect me. They say, ‘Oh, you have pretty good jiu-jitsu. Who is your professor?’” he adds, carrying a mock-Brazilian accent. “They expect me to say some stupid American dude. When I tell them Giva Santana, they all say, ‘Oh, man, he’s so good!’”

McCall also emphasizes the importance of Laercio Fernandes, a world-class BJJ player in the pluma division and one of Santana’s top students, as well as the fact that he now gets to work with Olympic Greco-Roman standout Shannon Slack.

“Laercio’s more my size, so I get to work with ‘Big Giva’ and ‘Little Giva,’” he says, “and now Shannon is making my wrestling even better.”

“Do you feel like there’s a renaissance happening at Team Oyama?” I ask. “It seems like it’s been forever since people thought of it as a major MMA team.”

“It makes me so happy to be part of that. I couldn’t do it in the WEC, but now the team has changed and we’re all making those steps. Me and Giva are going to be in the UFC,” McCall tells me with a gravity he seldom exhibits.

Act VI: Unspeakable Tragedy

“Justin Levens was one of my best friends. Sarah [McLean-Levens] was one of them, too,” McCall says after discussing some of the embattled training partners he has come across in the past.

Virtually any story involving Levens only ends up in one place, and it is neither a cheery nor happy one. Though it is hardly a symmetrical comparison, I am sure McCall has imagined the tragedy of Levens through the lens of Romeo and Juliet more than once.

“Justin actually bought a truck off of my family. Someone called me and said, ‘He hasn’t made a payment in six months. Go by the house,” McCall remembers.

“As I’m pulling up, I get a phone call. I was 200 yards away, and I knew. The cops were already there. I was the first friend. I got out, and they asked, ‘Who the f--- are you?’”

“I said, ‘That’s my friend’s house.’ The cop just looked back at me, and I knew. I sat down in the car and started to shake,” he says.

McCall remains remarkably cerebral in his description of events until this point.

“He shot his wife. Then he laid down next to her and shot himself. You know, um ..."

McCall’s voice trails off into the void. After a painfully pregnant pause -- four seconds that feel like a decade -- he continues.

“Some people call him a murderer; some people say it was love. The world is a f----- up place. I just say ...”

His voice trails off again, and he shows no signs of finishing the sentence.

“Do you ever try to make sense of it?” I ask quietly.

“No,” he interjects immediately. “There’s no point. At this point in my life, I’ve probably had 30 people -- people that I would say, ‘Hey, how are you?’ to on the street -- die. I’m 27.”

McCall’s expression is hard to explain. It looks like every emotion in the universe is competing for real estate on his face.

Act VII: Channeling Capulet

“What are you going to name your daughter?” I ask McCall.

“London,” he says with a nod and a smile.

“London ... what? What’s the middle name?” I inquire.

“Oh, Juliet!” he says with gusto. “I love Romeo and Juliet.”

McCall has “Capulet” tattooed across his chest, an ode to his love for Shakespeare’s timeless tragedy. Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 film adaptation of the play is his favorite film, and by a fair margin. His aesthetic -- most notably his messy, dégagé partial pompadour haircut -- is straight out of the film, previously worn by actor John Leguizamo’s character, Tybalt Capulet.

“Hey, everyone used to tell me I looked like John Leguizamo,” he says with a laugh. “Shay always makes fun of me, saying I look Mexican.”

McCall also has a rich sense of coincidence; he smiles, knowing my response.

“Capulet -- and you’re fighting a Montague,” I muse.

Finish Reading » Shakespeare Comes to the Cage -- Prosper or Peril

Related Articles