Vitor Belfort, From the Beginning

The Phenom Emerges

I was shooting the semifinals at the Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu National Championships on a sunny Sunday in November 1994 when Carlson Gracie Sr. approached me and said, “Keep an eye on that kid. He’s a phenom. He’ll win his weight division and the absolute.” Of course, I followed Gracie’s advice, and he was right. “Vitinho” defeated all of his opponents and captured gold medals in the heavyweight and absolute divisions for blue belt juveniles (under 18 years of age).

Advertisement

In that atmosphere of rivalry and toughness, they started to build Belfort. The rapid improvement he showed during no-gi training and the boxing skills he displayed -- Belfort started working with Claudio Coelho as a 12-year-old -- opened Gracie’s eyes. The world already knew his family but not Carlson himself, even though he had defended the family name in vale tudo upon Helio Gracie’s retirement and become the No. 1 producer of jiu-jitsu champion’s in the sport’s history; from the 1980s until the late 1990s, his grapplers won 90 percent of the competitions, from beginner to black belt.

When Frederico Lapenda invited Gracie to open an academy in

California, he surprised the entire team when he asked Belfort to

go with him. Opening Lapenda’s academy in West Hollywood made

Gracie recall the 1960s, when he had to defend the family name. The

United States provided Gracie’s team with exposure, and Belfort was

one of the primary vehicles. Whenever Gracie saw a big guy, he

invited him to visit the academy. Belfort lost count of how many

men he fought.

“I remember on day we just had lunch and a big wrestling guy came over,” Belfort told Sherdog.com. “I told Carlson that my stomach was totally full, and he told me to throw it up. He said, ‘If a man wants to pick up your girlfriend in the street, will you allow him to because your stomach is full?’” Belfort did as his teacher requested and submitted the man without using a single punch.

Without financial support through which to advertise, the academy in California started to mirror its Brazilian headquarters in Copacabana, with few students paying for private classes and a lot of police officers and security guards from the area training for free.

“Carlson’s heart was huge,” Belfort said. “Whenever he saw a big guy with potential to be a fighter, he invited him to train with us.”

Money was short, but the impressive sequence of tests made Gracie 100 percent sure that the time to take Belfort before the lions had come.

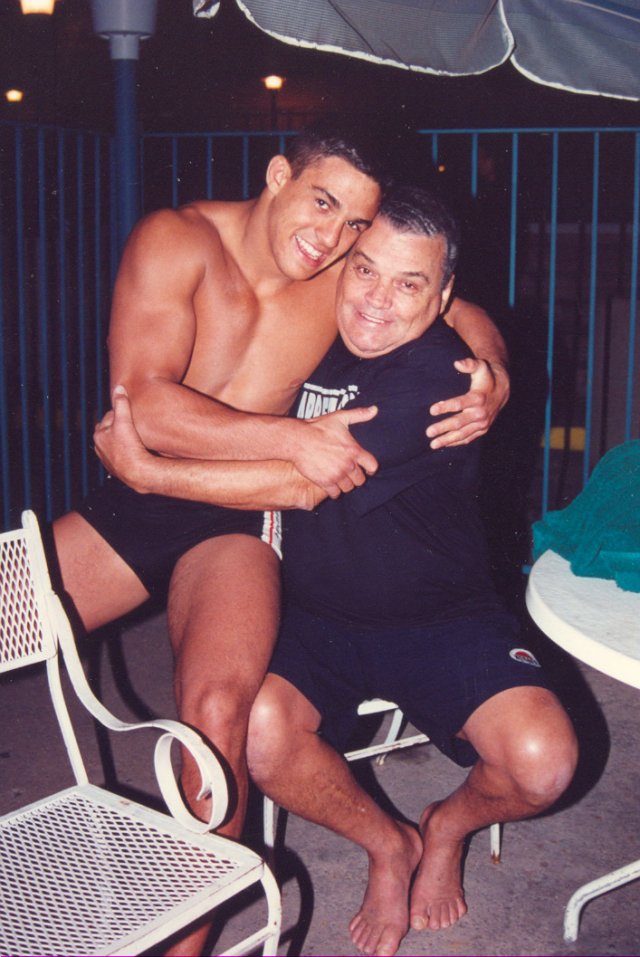

In April 1996, I traveled to Japan with Gracie to cover a Universal Vale Tudo Fighting event. When we returned from Tokyo, I spent five days at Gracie’s house in Los Angeles to follow Belfort’s training routine. After everything I had heard Gracie say about Belfort, I decided to write a story in “Tatame.” It was then that Gracie launched Belfort as his adopted son, and Vitor Belfort Gracie was born.

“I’m doing it as a marketing matter, because the Gracie name is very strong here in the United States,” Gracie told me. “He is able to beat anyone. It can be Marco Ruas, Hugo Duarte or Ken Shamrock. All those guys are welcome.”

By his mentor’s side, Belfort told me at that time that his dream was to conquer the Ultimate Fighting Championship and show the world that the Gracie name extended far beyond Royce Gracie and his immediate family.

“Carlson avenged Helio’s loss to Waldemar Santana and defended the Gracie name for 19 years, and nobody knows about him,” Belfort said. “That’s not fair, and I’ll fight to show how important Carlson Gracie is to martial arts.”

BRINGING A GUN TO A KNIFE FIGHT

A few months after that initial report was published in Brazil, Belfort traveled to Hawaii with his mother, Jovita, his mother’s boyfriend, Carlos Valente, and his sister, Priscila. Valente took Belfort to train at the Relson Gracie academy.

“One day I was training in there when some Pancrase guys showed up,” Belfort said. “Relson just had jiu-jitsu guys, and I offfered to train with them without a gi. In a few minutes, a guy was bleeding and asked to stop. I didn’t know he was a Pancrase champion. The Japanese magazine used many pages for that story.”

That training session resulted in an invitation to face the 6-foot-7, 295-pound Jon Hess at SuperBrawl 2 on Oct. 11, 1996. Hess had scored an impressive technical knockout against Andy Anderson at UFC 5. It would serve as Belfort’s professional mixed martial arts debut. At the weigh-in, Belfort was excited to see a number of Los Angeles Lakers were in attendance.

“I remember Shaquille O’Neal had just signed with the Lakers, and when he saw the name Carlson Gracie on my T-shirt, he bet a gold rolex with Magic Johnson, who asked me if I was crazy to fight that big guy,” Belfort said. “He accepted the bet. I’ll never forget about that.”

On the day of the fight, while Belfort was beginning his warmup in the dressing room, a representative from the promotion stepped forward with a request from Hess. According to Belfort, he wanted to propose special vale tudo rules, which would make attacks to the genitals and eye gouging legal.

“I said, ‘No, Carlson. I want to have a wife and kids someday,’” Belfort said. “Carlson immediately told me to shut up and told the translator to tell the guy that, besides vale tudo rules, we’d accept him bringing a knife to the ring. When the guy left the locker room, Carlson asked me, ‘Are you crazy?’ This guy’s afraid of you and wants to test your nerves. You’re going to kill him in less than a minute.’”

With more than six decades of vale tudo experience upon which to draw, Gracie’s words carried weight. Belfort entered the ring with confidence and knocked out Hess in 12 seconds.

THE OCTAGON BECKONS

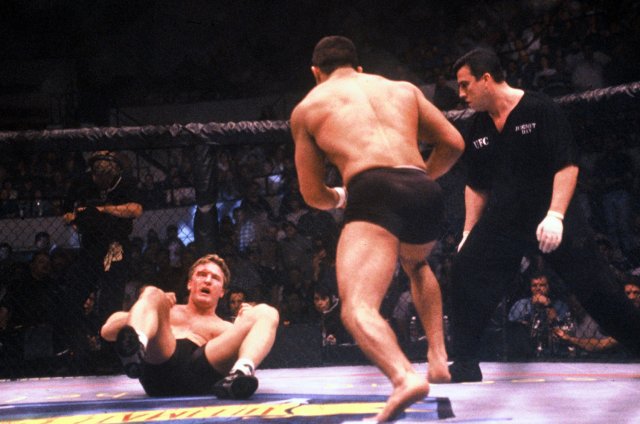

The impressive victory over Hess earned Belfort a ticket to the UFC four months later. Weighing 215 pounds by that time, Belfort entered the open weight tournament at UFC 12 and knocked out Tra Telligman and Scott Ferrozo in two minutes combined to win the competition. They called him “The Phenom,” and the legitimacy of the nickname was affirmed in May 1997, when Belfort knocked out David “Tank” Abbott in 43 seconds.

After three impressive wins in the UFC, the then 19-year-old Belfort was forced to confront an opponent with which he would become all too familiar throughout his career: fame. He was suddenly viewed as the No. 1 fighter from the Carlson Gracie camp, and jealousy spread among many of the teammates he grew up idolizing.

“It was not his intention, but Carlson ended up comparing me to almost all of the team,” Belfort said, “and it was hard to deal with all that envy.”

Stardom also bred complacency. In lieu of hard sparring, Belfort started following in the footsteps of friend and bodybuilder Curtis Leffler. In a few months, he had ballooned to 240 pounds, and he carried his newfound muscle into his matchup with UFC 13 tournament winner Randy Couture. They met at UFC 15 on Oct. 17, 1997, and the man affectionately known as “Captain America” smashed through Belfort in 8:16 for a decisive TKO victory.

“Definitely, the sudden fame affected me,” Belfort said. “I didn’t train anything for that fight. I was involved with many girlfriends, and even though he was tough, I was sure I could beat Couture easily. I paid the price for that. My world came crashing down, and it was a big shock for me.”

After a submission victory over Joe Charles in December 1997, Belfort made his recovery from the disappointing loss to Couture complete at UFC 17.5. There, he faced another future legend of the sport, Wanderlei Silva -- an International Vale Tudo Championship titleholder who was riding high after his knockout against Mike Van Arsdale. The self-confidence Silva and his team showed stood in stark contrast with Belfort, whose look of concern gave onlookers pause.

In only 44 seconds, Belfort took apart “The Axe Murderer” with one of the most unforgettable sequences of rapid-fire punches in MMA history. The crowd at Portuguesa Gymnasium in Sao Paulo, Brazil, went wild.

PARTING WAYS

Six months after he defeated Silva, Belfort shifted his attention to Pride Fighting Championships and a bout with Japanese icon Kazushi Sakuraba. It was an important chapter in the relationship between Belfort and Gracie. After a dominant start, Belfort broke his hand and the tide turned in Sakuraba’s favor.

“During his time, Carlson used to fight on cement courts without gloves for many hours,” Belfort said. “He could not accept that I fought worse with a broken hand.”

Gracie insinuated that Belfort was paid to lose, and upon their return to Brazil, mentor and pupil parted ways. Belfort threw out his anchor at Brazilian Top Team, the new camp formed by Liborio, Sperry, Bustamante and Bebeo Duarte, all black belt dissidents from the Gracie team. Gracie was angered by the move, but during that time, Belfort scored four straight wins in Pride over Gilbert Yvel, Daijiro Matsui, Heath Herring and Bobby Southworth.

Finish Reading » Belfort inadvertently raised Silva’s profile in Brazil with his challenge. Even though the UFC had grown in popularity in Brazil by 2011, only true MMA fans were fully aware of Silva. On the other hand, Belfort was a celebrity in the minds of most Brazilians. Brazilian media sent 46 journalists to cover UFC 126 on Feb. 5, 2011 in Las Vegas, guaranteeing one of the biggest MMA audiences ever in the country. Silva defended his middleweight crown in spectacular fashion, as he took care of Belfort with a front kick to the face and follow-up punches. Shock swept across the beaches, slums and countryside. No one, it seems, had envisioned “The Spider” beating Belfort so easily. Silva’s shadow widened overnight.

« Previous Vale Tudo Relics: The MMA Debut of Dan Henderson

Next Fabricio Werdum, From the Beginning »

More

Marcelo Alonso’s MMA Roots Series

Marcelo Alonso’s MMA Roots Series